By April 1941, the Luftwaffe Blitz on Britain was into its 6th month. Almost every night saw a night-time raid on a British target. The possibility of attacking more northern regions had opened up after the fall of France in the summer of 1940. The Luftwaffe could then reach targets in northern England, Scotland, and Northern Ireland.

On 5th April 1941, a briefing took place near a Luftwaffe base at Cambrai, France. Among those in attendance was Luftlotte Commander Field Marshall Albert Kesselring. Oberleutnant Walther von Siber recalled the event after the war’s end stating that Belfast was to be a target.

The first attack on Belfast came on the night of 7th-8th April 1941. That night, 517 Luftwaffe bombers took part in a raid targeting many British cities. A total of 3 bomber streams attacked the United Kingdom from bases in the Low Countries, northern France, and Norway. Primary targets for the evening were Glasgow, Clydebank, and Greenock. The Luftwaffe set secondary targets of Liverpool, Newcastle, and Dumbarton.

The weather was clear with a moderate wind across northwest Europe as the bomber crews left their bases. Luftwaffe intelligence predicted similar weather, ideal for bombing, across the United Kingdom. On arrival over the north of England and Scotland, however, crews found almost total cloud cover. The weather over Belfast was calm and clear, perfect for a raid. Light winds from the southeast and clear skies up to 20,000 feet gave the bomber crews a prime opportunity to target the city.

As Luftwaffe crews established their bearings and found new targets, bombs fell on Bristol, Plymouth, and London. Beginning at 2300hrs, the Irish Observation Corps noted the presence of Luftwaffe planes in Irish airspace. They informed the British authorities of movements along the east coast and also over Co. Cavan and Co. Tyrone.

With less than half of the Luftwaffe bombers finding their primary objectives, it is unknown whether the Luftwaffe intended to raid Belfast. Many of the planes involved in the raid may have diverted from other unsuitable targets. The presence of bombers from Kampfgruppe 26, an elite pathfinder squadron suggests that Belfast may always have been an intentional target that night.

The number of planes taking part in the bombing of Belfast remains unknown as Nazi authorities destroyed many records towards the end of the war. Over the night of 7th-8th April 1941, radar detected 13 plots of bombers over Belfast Lough and the Northern Irish coast. The Royal Navy reported to the Admiralty that Belfast suffered 7 small, distinct raids. No more than 8 Heinkel HE111 planes were overhead at any time.

Beginning of the Belfast Blitz

As the drone of the Heinkel planes began to fill the air, Constable Donald Fleck of York Road Royal Ulster Constabulary station was driving along the Shore Road. At Fortwilliam Park, he intercepted a military officer driving from the city with headlights on. The British Army officer home on leave warned the young police officer that a raid was imminent.

The leading enemy planes approached over the Co. Down coast from Ardglass via Bangor. They approached Belfast from the east following the water of Belfast Lough. Among the lead group were planes of Kampfgruppe 26, an elite pathfinder squadron based at Amiens, France. Their squadron records indicate they arrived over the city at 2250hrs. One crew dropped a 500kg high explosive bomb and 432 incendiaries from a height of between 1,200 and 3,500 metres. These resulting fires added to the moonlight and the glow from the still operational lighthouses, illuminating the docks. Some witnesses reported at least 2 of the planes left their navigational lights on showing a disregard for the anti-aircraft gun crews.

At 0001hrs on 8th April 1941, barrage balloon positions around the city marked the beginning of the raid. The first high explosive bombs and incendiary devices fell at around 0005hrs. The diaries of 5th Battalion Royal Irish Fusiliers based at Knock, Co. Down begin the raid at 0015hrs. Another regiment observing the raid was 13th Battalion Royal Welch Fusiliers in Bangor, Co. Down. They observed a bright red glow on the horizon that fluctuated throughout the raid beginning as early as 0010hrs.

Suddenly I heard a long roaring whine and next moment a hell of a thud. I knew at once it was something out of the ordinary and went upstairs to the attic and standing on a box, opened the skylight. Something in my stomach seemed to drop, for the whole length of the shipyard was ablaze with stark white light. The guns all over the city began to roar. I knew it was our first raid.

Diary of William McCready, Keadyville Avenue, Belfast, Co. Antrim, 8th April 1941.

Diarists including Moya Woodside, Doreen Bates, JC Beckett, and Sir Wilfred Spender suggest the first bombs fell before they heard anti-aircraft fire or the sounding of air-raid sirens. Military diaries agree, stating the first alarm sounded at 0011hrs, 10 minutes after the attack began.

During the course of the raid, Luftwaffe bombers attacked from around 7,000 feet. This fell between the 2,000 feet limit of the barrage balloons and the 12,000 feet limit of the anti-aircraft guns.

The first casualty of the Belfast Blitz was an Air Raid Warden injured by shrapnel as he made his way to his post. He received treatment at the first-aid post at Mersey Street Public Elementary School.

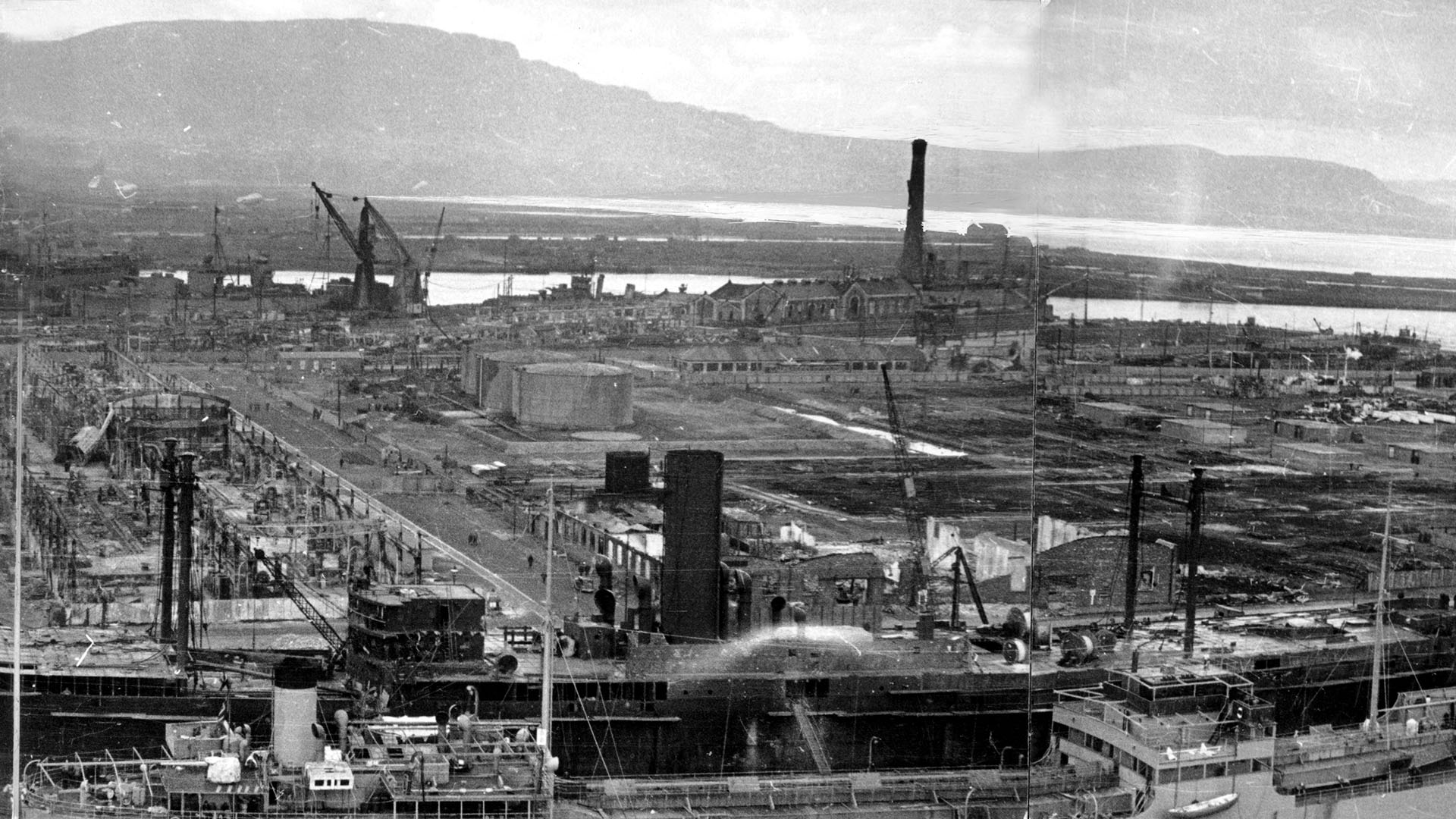

The docks and the shipyard under attack

Throughout the early hours of 8th April 1941, the Luftwaffe attacked the docks area with great accuracy. Despite the area’s significance to industry and the war effort, defences were inadequate. The docklands contained a large amount of high flammable material including coal, tar, timber, and grain. The first wave of the attack ignited at least a dozen fires in the vicinity.

Among the premises damaged in the docks area was the timber yard of McCue, Dick and Co. Ltd. The yard was ablaze by 0015hrs and by the time firefighters arrived at 0130hrs, flames engulfed the yard. It was one of the most intense fires anywhere in the United Kingdom on that night’s raid. Fireman FE Watson’s crew battled the flames for more than an hour before giving up. Other timber yards in the area began to burn. Many timber companies had yards in the area including Ruddell, Harvey, and Co. Ltd., Hendron Bros., Robb Bros., William Davidson, and Lyttle and Pollock Ltd. Fires also broke out at Imperial Chemical Industries Ltd., W Clements’ Soap Manufacturers, and the London Midland and Scottish Railway Stabling Yard.

On Northern Road, 5 bombs fell within 30 yards setting fire to grass and bracken. This added to the conflagration, helping to guide the next waves of bombers to their targets. Around half a dozen bombs fell on the Pollock Basin, Herdman Channel, and Victoria Channel. These damaged gantries, cranes, stairs, roofs, and girders, as well as larger buildings. Worse was to come for the shipyard though as high explosive bombs, parachute mines, and incendiaries continued to fall from planes approaching in waves at half-hourly intervals.

Civil Defence

At Belfast Corporation Fire Brigade Station on Chichester Street, Station Master Paddy Donnelly directed crews to the docks area. Among the firefighters was Jimmy Mackey. His crew began putting out fires on Milewater Road and Duncrue Street as heavy explosives began to fall. When firefighters arrived at many of the fires, they ran out hoses only to find water mains cracked and damaged by the bombing. In some areas, little or no water was available to tackle the blazes.

Mackey was present when a group of firefighters ran towards a parachute thinking it to be a Luftwaffe airman. As what turned out to be a parachute mine drew closer, the realisation set in. The firefighters turned and ran and Mackey threw himself to the ground, in the safety of a nearby drain. That bomb claimed the lives of the first 2 victims of The Docks Raid. They were a pair of young Auxiliary Fire Service volunteers; Archibald McDonald of Percy Street, and Brice Harkness from Cookstown, Co. Tyrone. A first-aid party based at a nearby school recovered their bodies later that morning.

Although the main target of the attack was the docks area, residential housing in the neighbourhoods suffered too. Rows of densely populated, working-class housing sustained significant damage. Wardens in these areas led many residents to shelters where they spent the hours until the all-clear. Fortunately, no shelters took a direct hit, as they were not built to withstand devices of the size of the falling parachute mines.

Bombs on Belfast

In East Belfast, around 800 incendiaries fell on the Newtownards Road, Albertbridge Road, and Templemore Avenue. High explosive bombs also fell but it was the firebombs that caused the most damage in the area. Many incendiaries burned out in back gardens or in the street but around 150 smashed through the roofs of houses. Residents, for the most part, dealt quickly with the flames using sandbags, stirrup pumps, and buckets of water. Wartime publicity videos on how to deal with an incendiary device had worked it seemed.

Having earlier left the docks, beaten by the blaze at McCue, Dick, and Co. Ltd., fireman FE Watson and his crew received a call to provide backup at Albertbridge Road Fire Station. On the way, angry residents of the Newtownards Road demanded they stop and put out the fires in the area. Around a dozen fires burned in the neighbourhood at the time, including a quickly extinguished blaze on the roof on the Templemore Baths.

The worst, however, was at St. Patrick’s Church of Ireland on the Newtownards Road. Wardens based on the premises watched helplessly as the old pine gallery lit up, as did the wooden pews and floor. Even the Air Raid Precautions post on site burned out. Only the altar and east window escaped the worst of the flames that left the building little more than a shell. Dark stains remain on some of the church’s timbers, a remnant of the tragedy of the Belfast Blitz. In misinformation that followed the attack, a Priest from St. Patrick’s Church on Donegall Street heard to his surprise that bombs hit his church killing 50-60 parishioners.

High explosives and incendiaries also fell in North Belfast. Areas off the Shore Road and York Road sustained considerable damage. Half a dozen bombs fell near an anti-aircraft gun emplacement at Grove Park Playing Fields. One exploded on poorly constructed housing opposite the park, between Fife Street and Arosa Parade. It all but destroyed the houses, setting them alight but the residents emerged unhurt. Along another side of the park, a bomb exploded on Alexandra Park Avenue. It left a crater 15 feet wide and 2 feet deep in the road but not a single window nearby shattered.

Not all the bombs exploded, and volunteers at a nearby first-aid post at Grove Elementary School vacated to Mountcollyer School, half a mile away. Another unexploded device led to the evacuation of around 200 people. Others did not escape in time and one man in the area enjoying a late-night bath found himself in the street as a result of the blast.

West Belfast escaped the worst of The Docks Raid. At St. Paul’s Parish on the Falls Road, Reverend Dr. James Dean Hendley made only a small note referring to the raid. The Priest writing in the Domestic Chronicles of Clonard Monastery noted:

A big raid by several German planes took place on this night, lasting some hours. We went to the cellar. Big damage was done by bombs in the docks and a great conflagration could be observed from the monastery windows.

Some residents of South Belfast barely acknowledged a raid had taken place. Among them was diarist Moya Woodside, who refused to leave her bed despite the insistence of her ex-military Captain husband.

I stayed where I was. We have had so many false alarms that in my drowsy state, I muttered something about it being only anti-aircraft fire. I could not hear planes and came to the conclusion that this was some sort of practice. In the morning, I was astonished to hear from my husband that there had been a genuine raid and that he had been called to the hospital as additional staff to aid with the large number of injured. We only live about 1.5 miles away. It seems amazing that all this can have happened so near while I lay calmly in bed.

The end of the raid

As the raid went on, waves of bombers attacked in half-hourly intervals. At 0200hrs, diarist William McCready left his home in Keadyville Avenue during a lull and walked to the top of Premier Drive. From there, he could view the fires at the docks. The attacks continued until a little after 0300hrs. All went quiet and many thought it to be the end of the raid but they were wrong. A pair of huge explosions were yet to come and they would be among the most devastating of the raid, taking out 2 key targets in the shipyard area.

Those bombs fell from the Heinkel HE111 of Oberleutnant Siegfried Rothke, a Luftwaffe Pilot of Kampfgruppe 4. He was under orders to bomb Dumbarton on 8th April 1941. His secondary targets were Liverpool or Newcastle and when he took off from Utrecht, Netherlands shortly before 0000hrs, he carried a pair of 1,000kg parachute mines. He reached Glasgow by 0215hrs and confirmed the weather was unsuitable for visual bombing. Reports suggested the north of England was no better. The Luftwaffe offered experienced Pilots a level of discretion and, noticing clear skies over the Irish coast, Rothke switched course to Belfast.

His plane arrived over the city after 0300hrs. Clear skies and the already burning fires made picking his targets easier. By this stage, around 20 fires including that at McCue, Dick, and Co. Ltd. had come together in one large inferno. Approaching above the barrage balloon cover, at a height of 1,900 feet, he released the parachute mines at 0322hrs.

The first descended slowly over the Rank Flour Mill on Northern Road. A group of nightshift workers watched it fall and ran to the main building to shelter. The resulting blast tore apart the steel and asbestos sheds around the mill injuring 20 workers and trapping a further 15 in the debris. The second parachute mine caused even more devastation as it caught in the wind and floated over the Short and Harland Aircraft Factory and across the Musgrave Channel. It exploded on the rooftop of the Alexandra Works aeroplane fuselage factory at Harland and Wolff on Queen’s Road. Nightshift workers also watched it descend, having left their shelters believing the raid to be over. A group of them ran towards the parachute believing it to be a Luftwaffe airman, just as firemen McDonald and Harkness had earlier in the night. Of these men, 5 died in the blast and the remaining injured later received treatment at the Royal Victoria Hospital.

The force of this blast threw Air Raid Warden Jimmy Doherty off his feet and into the door of a bar. He was on Clifton Street, over a mile away from the point of impact and the shockwaves rattled the bottles and glasses inside the public house. Such a forceful explosion was devastating in the shipyard area. Shoddily built brick walls and “Belfast” roofs made of wood and felt collapsed and burned across the 4.5-acre Harland and Wolff site. Inside the buildings, the fuselages of 50 Short Stirling Bombers became a tangle of wreckage. Fires soon spread across the site, and as Rothke began his return journey, he claimed the flames remained visible for up to 20 minutes. As far away as Ballymena, Air Raid Precautions Messenger James Kyle noted the orange glow in the sky.

Once again, the fire engine of FE Watson arrived on the scene, joining other crews in dousing the flames. There was no chance of saving the fuselage building but crews working from high gantries prevented the fire from spreading to a nearby paint shop. They also extinguished a fire on scaffolding surrounding an almost completed merchant ship. Another support scaffold had snagged a parachute mine and received a wide berth by the crews as they dealt with dud bombs and unexploded devices.

The last bombs of The Docks Raid fell at around 0325hrs on 8th April 1941. On returning to base in northern France, one crew recorded Belfast’s defences as:

Inferior in quality, scanty, and insufficient.

Anti-aircraft guns around the city fired around 700 rounds scoring no direct hits on enemy aircraft. Shrapnel caused damage to 3 barrage balloons and at a battery at Balmoral Golf Club, a Gunner became an early victim of the raid. A misfiring gun claimed the life of the Gunner and left 4 others requiring hospital treatment. Gunner Godfrey Lindsay of Holywood, Co. Down was on the scene and witnessed the aftermath of the incident, noting the strong smell of cordite in the air. Elsewhere, other service personnel found themselves injured in the chaos.

In the docks, around a dozen vessels joined in the anti-aircraft fire, expending over 840 rounds of ammunition. Rear Admiral Richard King reprimanded those involved for wasting ammunition. They had been ordered to hold fire unless the Luftwaffe dive-bombed the docks.

At 0358hrs, those who sought refuge in shelters emerged after the sounding of the all-clear. In much of the north and east of the city, the streets were unrecognisable. For hundreds of yards in all directions, windows and roofs were shattered, and gable walls cracked. The slate, glass, and brickwork rubble was knee-deep in some streets. Within half an hour of the all-clear, most fired were out. Treatment of the injured and recovery of those less fortunate took place, and the citizens of Belfast became accustomed to life after a Luftwaffe raid. Much worse was to come.